No branches? No problem — a Forth assembler

The set of words available after Miniforth boots is quite bare-bones. One reader even claimed that, since there's no branches, it is not Turing-complete, and therefore not worthy of being called a Forth! Today is the day we prove them wrong.

In the previous post, I described the bootsector-sized core of Miniforth, with all the clever optimizations I've had to use to fit it in. To recap, the following words are available:

+ - ! @ c! c@ dup drop swap emit u. >r r> [ ] : ; load s:

Most of those will be familiar to Forth programmers, but load and s: might

need some comment. load ( u -- ) is a standard word from the

optional Block word set — it loads block u and executes it as Forth source

code.1 This word is crucial for practical use of such a small

Forth, as once you bootstrap far enough, you can save your code to disk, and

after a reboot, resume with just 1 load.

To get to that point, however, you need to write quite a bit of code. To make

the source code available in memory once you can save it, I included

s: ( buf -- buf+len ), which is essentially a string poke — the rest of the

input buffer is copied to buf. The address of the end of the buffer is

left on the stack, such that you can use s: on the next line, and the result

will be concatenated.

In this post, we will start from the state Miniforth boots up in, and:

- write a Forth-style assembler,

- bootstrap the ability of writing to disk, and

- use our assembler to implement branches.

This is not to say that this is the only way. I do have a pure-Forth implementation of branches on top of Miniforth, and I intend to talk about it more in about a week — meanwhile, I encourage you to try figuring it out on your own. I'm really curious how many different approaches there are.

Meanwhile, let's explore the approach that doesn't discard most of the performance in the name of purity. For reference and easy experimentation, the code from this post is available on GitHub. When explaining the code, I'll sometimes add comments, but since we didn't implement any comment handling yet, they aren't actually there in the code.

s: — the workflow

I've decided to keep my source code at address 1000, in the space between the

parameter and return stacks. The first thing we'll need is a way of running the

code we put there. The InputPtr is defined to be at A02, so let's define

run, which pokes a value of our choice at that address:

: >in A02 ; : run >in ! ;

>in is a traditional name for the input buffer pointer, so I went with

that.2 To make sure it is also available on subsequent boots, I save this

piece of code in memory:

1000 s: : >in A02 ; : run >in ! ;

This is a good time to peek at the current pointer to the source buffer, with

dup u.. Unless you added some writespace, the answer will be 101A, and this

is the address we will want to pass to run later on, to avoid redefining >in

and run.3

After writing enough code to want to test it, I would print the current address

of the buffer with u., and then run the new code from the previous printed

buffer address. At first, it's important that the buffer address is not left at

the top of the stack, as Miniforth boots up with the addresses of the built-in

system variables on the stack, and we will want to access those.

System variables

In fact, almost everything we want to do requires these variables, so let's take care of that first — having to dig into the stack every time you need one of these variables is unworkable. The stack starts out like this:

latest st base dp disk#

Normally, we would just do constant disk#, constant here, and so on.

However, we do not have constant, or any way of defining it (yet).

literal is closer, but we'd need at least here to implement it

and latest to mark it as immediate. We can work around the immediate issue

with [ and ], which suggests the following course of action:

swap : dp 0 [ dup @ 2 - ! ] ;

Let's go through this step by step, as the way this works is somewhat intricate.

dp stands for data pointer. It is the variable backing here, the

compilation pointer, meaning here is simply defined as

: here dp @ ;

When the code inside square brackets executes, our memory looks like this:

What we wish to do is put dp where the 0 currently is. Since we ran a swap

before defining our word, the address of dp is at the top of the stack. After

dup @ 2 -, we will have a pointer to the cell containing the 0, and ! will

overwrite it. As you can see, the 0 doesn't have any particular significance,

we could've used any literal.

Next up, we define cell+ and cells. The reason I do it this early is that

one of the things I would eventually like to do is switch to 32-bit Protected

Mode, so as much code as possible should be cell-width agnostic.

: cell+ 2 + ;

: cells dup + ;

Also, since we now have dp, let's write allot. The functionality of

incrementing a variable can be factored out into +!:

: +! ( u addr -- ) dup >r @ + r> ! ;

: allot ( len -- ) dp +! ;

This allows defining c, and ,, which write a byte or cell, respectively,

to the compilation area:

: c, here c! 1 allot ;

: , here ! 2 allot ;

Next, we will write lit,, which appends a literal to the current definition.

To do this, we need the address of LIT, the assembly routine that handles a

literal. We store it in the 'lit "constant", with a similar trick to what we

did for dp:

: 'lit 0 [ here 4 - @ here 2 - ! ] ;

: lit, 'lit , , ;

This lets us easily handle the rest of the variables on the stack:

: disk# [ lit, ] ;

: base [ lit, ] ;

: st [ lit, ] ;

: latest [ lit, ] ;

I'm calling it st instead of state, because state should be a cell-sized

variable where true means compiling, and st is a byte-sized variable where

true means interpreting.

Custom variables

If you're in the mood for mischief, you can create variables out of thin air by

simply mentioning them. The lack of error checking will turn them into a number,

essentially giving you a random address. For example, srcpos u. outputs

DA9C. Of course, you're risking that these addresses will collide, either with

one another, or with something else, such as the stack or the dictionary space.

I wasn't in the mood for mischief, so we'll do this properly. The core of any

defining word will be based on :, as that already parses a word and creates a

dictionary entry. We just need to go back to interpretation mode. [ does that,

but it's an immediate word, and we can't define postpone yet, so let's define

our own variant that isn't immediate:

: [[ 1 st c! ;

We will also need a non-immediate variant of ;. The only thing it needs to do

compile exit. We don't know the address of exit, but we can read it out of

the most recently compiled word:

here 2 - @ : 'exit [ lit, ] ;

For example, here's how we'd use it for constant:

: constant \ example: 42 constant the-answer

: [[ lit, 'exit ,

;

create defines a word that pushes the address directly afterwards. The typical

use is

create some-array 10 cells allot

To calculate the address we should compile, we need to add 3 cells — one for

each of LIT, the actual value, and EXIT.

: create : [[ here 3 cells + lit, 'exit , ;

variable, then, simply allots one cell:

: variable create 1 cells allot ;

Improving on s:

So far, the pointers passed to s: and run have had to be managed manually. It's

a simple process, though, so let's automate it. srcpos will contain the

current end of the buffer, and checkpoint will point at the part that hasn't

been ran yet.

variable checkpoint

variable srcpos

The automatic variant of s: is called s+:

: s+ ( -- ) srcpos @ s: dup u. srcpos ! ;

We also print the new pointer. This has two uses:

- if you make a typo and want to correct, you can just read the approximate address where you need to poke around;

- we need to make sure that no definition straddles a kilobyte boundary, so that our buffer can be directly written into blocks.

The pending portion of the buffer can be executed with doit:

: move-checkpoint ( -- ) srcpos @ checkpoint ! ;

: doit ( -- ) checkpoint @ run move-checkpoint ;

Setting this up amounts to something like

1234 srcpos ! move-checkpoint

This line is not written to disk, as the exact address is not going to be useful after a reboot.

Forth-style assemblers

The usual syntax of assembly looks like this:

mov ax, bx

If we wanted to handle that, we'd need to write a fancy parser, and there's no way we're going to be able to do that without branches. Let's adjust the syntax for our uses instead — if AT&T is allowed to do that, so can we. To be specific, let's make each instruction a Forth word, passing the arguments through the stack:

bx ax movw-rr,

I chose to order the arguments as src dst instr,, with the data flowing

left-to-right. This is consistent with how data flows in normal Forth code, and

is an exact mirror of Intel's syntax. After a dash, I include the types of the

arguments, in the same order — register (r), memory (m), or immediate (i).

Finally, instructions that can be both byte and word-sized have a b or w

suffix, like in AT&T syntax.

Note that having to specify the operand types manually isn't a fundamental limitation of Forth assemblers. Usually, nothing prevents building in more smarts into these words to pick the right variant based on the operands automatically. However, in this particular case, we don't have any branching words (as they are our goal 😄).

x86 instruction encoding

The simplest to encode are the instructions that don't take any arguments. For example,

: stosb, AA c, ; : stosw, AB c, ; : lodsb, AC c, ; : lodsw, AD c, ;

Next simplest are instructions that include immediates — numeric arguments that come immediately after the opcode:

: int, CD c, c, ;

Some instructions use a bitfield in their opcode byte. For example, an immediate load such as mov cx, 0x1234` encodes the register in the lower 3 bits of the opcode:

The registers map to the following numeric values:

: ax 0 ; : cx 1 ; : dx 2 ; : bx 3 ; : sp 4 ; : bp 5 ; : si 6 ; : di 7 ;

You read that right, it goes AX CX DX BX. As far as I know, this is not

because somebody at Intel forgot their ABC's, but because the etymology of these

register names goes something like "Accumulator, Counter, Data,

Base", and the fact that they're the first four letter is just a

coincidence. Or that's the jist of it, anyway. This retrocomputing.SE

post includes some speculations on how it could be beneficial to the

hardware design, but no hard facts.

The corresponding numbering for byte-sized registers looks like this:

: al 0 ; : cl 1 ; : dl 2 ; : bl 3 ; : ah 4 ; : ch 5 ; : dh 6 ; : bh 7 ;

Thus, we can encode some movs:

: movw-ir, B8 + c, , ;

: movb-ir, B0 + c, c, ;

These can be used like so:

ACAB bx movw-ir,

42 al movb-ir,

Note that it is the responsibility of the user to use an 8-bit register with

movb, and a 16-bit register with movw.

Some other instructions that are encoded in this way are incw/decw and

push/pop:

: incw, 40 + c, ;

: decw, 48 + c, ;

: push, 50 + c, ;

: pop, 58 + c, ;

ModR/M

The most complex instructions we'll have to deal with make use of the ModR/M

byte. This is the encoding mechanism responsible for instructions like add ax, [bx+si+16], but also ones as simple as mov ax, bx.

The opcode itself specifies a pattern, such as mov r16, r/m16. In this case,

it means that the destination is a register and the source is either a register

or the memory. The ModR/M byte, which comes after the opcode, specifies the

details of the operands:

The three bits in the middle specify the r16 part, while the rest specifies

the r/m16 part, according to this table:

| reg/[regs] field | mod: 00 | mod: 01 | mod: 10 | mod: 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | [BX+SI] | [BX+SI+d8] | [BX+SI+d16] | AL/AX |

| 1 | [BX+DI] | [BX+DI+d8] | [BX+DI+d16] | CL/CX |

| 2 | [BP+SI] | [BP+SI+d8] | [BP+SI+d16] | DL/DX |

| 3 | [BP+DI] | [BP+DI+d8] | [BP+DI+d16] | BL/BX |

| 4 | [SI] | [SI+d8] | [SI+d16] | AH/SP |

| 5 | [DI] | [DI+d8] | [DI+d16] | CH/BP |

| 6 | [d16] | [BP+d8] | [BP+d16] | DH/SI |

| 7 | [BX] | [BX+d8] | [BX+d16] | BH/DI |

As you can see, if the mod field is set to 3, then the lower 3 bits just

encode another register, in the same order as before. Otherwise, we choose one

of the eight possibilities for address calculation, with an optional offset

that can be either 8 or 16 bit. Said offset comes directly after the ModR/M

byte, and is sign-extended to 16 bits if necessary.

There is one irregularity, in that if we try to encode a [BP] without any

offset, what we get instead is a hardcoded address, such as mov bx, [0x1234],

which should come after the ModR/M byte itself.4 If you recall, the

lack of [BP] is why switching the return stack to use DI instead was

beneficial.

A peculiar aspect of this encoding is that register-to-register operations can

be encoded in two different ways. Let's take xor cx, dx, for example:

Anyway, let's implement this. First, the register-to-register variant. I chose

to name the word for compiling such a ModR/M byte rm-r,, meaning that there is

a register in the field that could also be memory, followed by another

register. We don't have any bitshifts, but we can work around that with

repeated addition:

: 2* dup + ;

: 3shl 2* 2* 2* ;

: rm-r, ( reg-as-r/m reg -- ) 3shl + C0 + c, ;

When using rm-r,, we need to make sure that the opcode used is the one with

the r/m16, r16 template — we would need to swap the two registers otherwise:

: movw-rr, 8B c, rm-r, ;

: addw-rr, 03 c, rm-r, ;

: orw-rr, 0B c, rm-r, ;

: andw-rr, 23 c, rm-r, ;

: subw-rr, 2B c, rm-r, ;

: xorw-rr, 33 c, rm-r, ;

: cmpw-rr, 3B c, rm-r, ;

Memory-to-register variants aren't much harder. We define the addressing modes, just like we did for registers.

: [bx+si] 0 ; ; [bx+di] 1 ; ; [bp+si] 2 ; ; [bp+di] 3 ;

: [si] 4 ; ; [di] 5 ; ; [#] 6 ; ; [bp] 6 ; ; [bx] 7 ;

[#] is the absolute address mode, which should be used by assembling the

address manually after the instruction, for example

[#] ax movw-mr, some-addr ,

I also include [bp], which collides with [#], as the address mode words can

be shared with the [??+d8] and [??+d16] modes.

Analogously to rm-r, we have m-r,:

: m-r, ( mem reg -- ) 3shl + c, ;

r-m, is the same, just swap the operands:

: r-m, ( reg mem -- ) swap m-r, ;

There is no need to define every instruction with memory operands, just movs

are enough:

: movw-mr, 8B c, m-r, ;

: movw-rm, 89 c, r-m, ;

There is also one slightly different use of the ModR/M byte. Namely, if an

instruction only needs one operand (such as not bx or jmp ax), only the

r/m one is actually used. In that case, the register field is instead reused

as more bits for the opcode itself.

The notation used by Intel's manual for this is opcode /regbits. For example,

an indirect jump is FF /4, while an indirect call is FF /2, sharing the

main opcode byte. We can encode instructions like these by simply pushing the right

value before calling rm-r,.

: jmp-r, FF c, 4 rm-r, ;

: notw-r, F7 c, 2 rm-r, ;

To actually assemble a primitive word, we'll also need a way of creating its

header. The simplest way to do that is to call the normal :, and then rewind

dp by three bytes, to remove the call to DOCOL:

: :code : [[ here 3 - dp ! ;

To finish such a definition, we compile a NEXT:

: next, lodsw, ax jmp-r, ;

Note that next, is not defined with :code — it is the equivalent of an

assembler macro.

As an example of a simple assembled primitive, let's look at the implementation

of 1+:

:code 1+ bx incw, next,

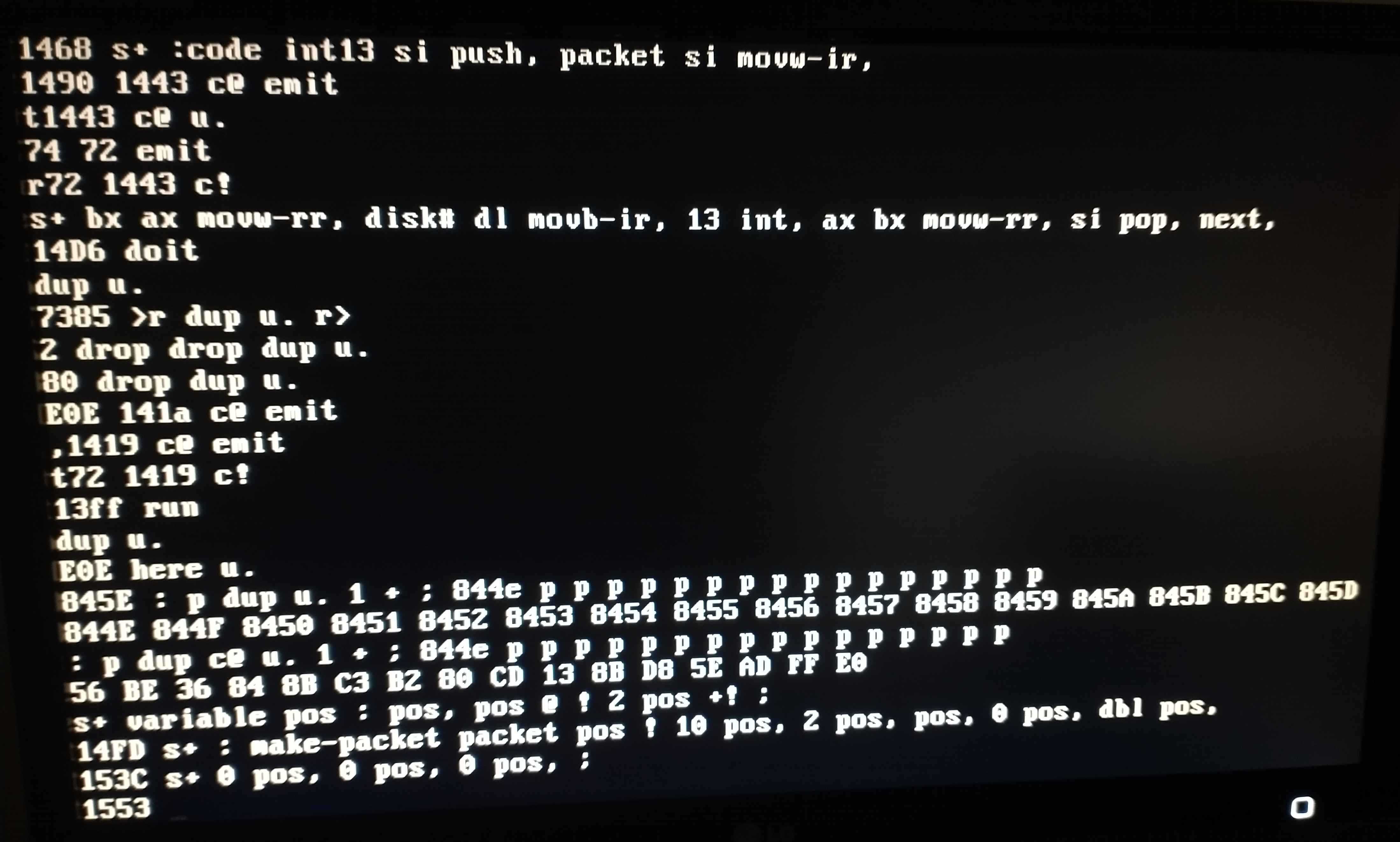

Disk I/O

This is actually enough to write our work to disk. Just like the implementation

of load, we'll need to create a disk address packet, and then call int 0x13.

One primitive word can serve for both reading and writing, as the only

difference is the value of AX you need. It is crucial to preserve SI — I've

had the displeasure of learning this empirically.

create packet 10 allot

:code int13

si push, \ push si

packet si movw-ir, \ mov si, packet

bx ax movw-rr, \ mov ax, bx

disk# dl movb-ir, \ mov dl, disk#

13 int, \ int 0x13

ax bx movw-rr, \ mov bx, ax

si pop, \ pop si

next,

Note that we're saving the returned value of AX back on the stack. This is

because a non-zero AH value signals an error.

To fill the packet with data, I'm using a variant of , that writes to a

controlled location instead of here:

variable pos

: pos, ( val -- ) pos @ ! 2 pos +! ;

: make-packet ( block buffer -- )

packet pos !

10 pos, \ size of packet

2 pos, \ sector count

pos, 0 pos, \ buffer address

2* pos, 0 pos, 0 pos, 0 pos, \ LBA

;

For reading, we use AH = 0x42, as before. Writing uses AH = 0x43, but in

that case the value of AL controls whether we want the BIOS to verify the

write — we do, so I've set it to 0x02.

: read-block make-packet 4200 int13 ;

: write-block make-packet 4302 int13 ;

Precautions

It would be nice to verify that our new code was assembled correctly before running it. Ideally, we'd write a little hexdump utility, but we still don't have any way to loop. There is a way around that, though — just type in the word you need many times in a row:

: p ( buf -- buf+1 ) dup c@ u. 1 + ;

\ later...

here 10 - p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p drop

Another good sanity check is to make sure that nothing we weren't expecting has

been pushed onto the stack — those are usually caused by undefined words being

badly turned into numbers. The way to do this is dup u. — an empty stack will

result in a response of E0E, stemming from a benign stack underflow we've just

caused. One example of a bug this has once caught is a typo, where I had typed

movb-it, instead of movb-ir,.

The first disk access I tried was 0 4000 read-block u. 41fe @ u.. This shows the

AA55 magic number at the end of the bootsector. I then wrote my source code to

blocks 1 and 2, and read them into a separate buffer to make sure it worked. In

hindsight, it might've been a good idea to read a block other than 0 before

attempting a write, to make sure that providing the LBA is working properly.

Thankfully, this particular bug was purely hypothetical.

I also wrote the same data to blocks 0x101 and 0x102. That way, I can recover if I ever break booting from the usual block numbers.

Jumps

Before we tackle implementing branches, we'll need one more instruction — the conditional jump. On x86, the jump offsets are encoded as a signed value relative to the current instruction pointer. There are different encodings for different bit widths of this value, but we'll only need the shorter 8-bit one.

To be specific, the value is relative to the end of the jump instruction, so that it matches the number of skipped bytes in the case of forward jumps:

To assemble the jump distances, I use two pairs of words — one for forward jumps, and one for backward ones:

jnz, j> ... >j \ forward jump

j< ... jnz, <j \ backward jump

The rule is that the arrows show the direction of the jump, and the arrows must

be "inside" — in other words, if you got the two words next to each other, these

arrows should fit like a glove. The two words simply communicate through the

stack. For example, j< will simply remember the current location:

: j< here ;

This is then consumed by <j, which subtracts the current position and compiles

the offset:

: <j here 1 + - c, ;

For forward jumps, we compile a dummy offset, to rewrite it later:

: j> here 0 c, ;

: >j dup >r 1 + here swap - r> c! ;

Finally, the jump instructions themselves. Some of the jumps have multiple

names. For example, since the carry flag gets set when a subtraction needs to

borrow, a jc has exactly the same behavior as the unsigned comparison jump

if below. The same applies to je and jz, but that's intuitive enough for

me, so I didn't feel the need to define both names.

: jb, 72 c, ; ; jc, 72 c, ; ; jae, 73 c, ; ; jnc, 73 c, ;

: jz, 74 c, ; ; jnz, 75 c, ; ; jbe, 76 c, ; ; ja, 77 c, ;

: jl, 7C c, ; ; jge, 7D c, ; ; jle, 7E c, ; ; jg, 7F c, ;

Branches

When compiled into a definition, branches look like this:

By convention, words that get compiled into a definition but aren't used

directly have their names wrapped in parentheses, so our branches are called

(branch), which is unconditonal, and (0branch), which pops a value off the

stack and branches if it's zero.

We can read the branch target out of the pointer sequence with lodsw:

:code (branch)

lodsw, \ lodsw

ax si movw-rr, \ mov si, ax

next,

In the case of the conditional branch, it is important to remember to always read (or skip) the branch target, regardless of whether the branch condition is true.

:code (0branch)

lodsw, \ lodsw

bx bx orw-rr, \ or bx, bx

jnz, j> \ jnz .skip

ax si movw-rr, \ mov si, ax

>j \ .skip:

bx pop, \ pop bx

next,

To handle branch offset computation, I use a very similar set of words to the ones used by jumps. The implementation is simpler, though, since the encoding isn't relative to the current position:

: br> here 0 , ;

: >br here swap ! ;

: br< here ;

: <br , ;

Control flow

To make the logic that compiles ifs actually run at compile time, we need to

mark these words as immediate. To do that, we use immediate, which sets the

immediate flag of the most recently compiled word:

: immediate ( -- )

latest @ \ get pointer to word

cell+ \ skip link field

dup >r c@ \ read current value of the length+flags field

80 + \ set the flag

r> c! \ write back

;

We'll also need compile, which, when invoked as compile x, appends x to

the word currently being compiled. We don't actually need to make it an

immediate word which parses the next word by itself, simply reading out the

address of x like lit or (branch) do it is enough:

: compile r> dup cell+ >r @ , ;

if is simply a conditional forward branch:

: if compile (0branch) br> ; immediate

: then >br ; immediate

else is a bit more complicated. We need to compile an unconditional branch

jumping to the then, but also resolve if's jump to point just after the

unconditional jump. I like using the return stack manipulation words for this,

as the arrows match the ones used by >br and make the code easier to read:

: else >r compile (branch) br> r> >br ; immediate

Next, we need loops. Firstly, the simple begin ... again infinite loop:

: begin br< ; immediate

: again compile (branch) <br ; immediate

begin ... until isn't much harder — just use a conditional jump at the end:

: until compile (0branch) <br ; immediate

Lastly, Forth's unique begin ... while ... repeat loop, where the loop

condition is in the middle of the loop:

: while ( backjmp -- fwdjmp backjmp )

compile (0branch) br> swap

; immediate

: repeat ( fwdjmp backjmp -- )

compile (branch) <br >br

; immediate

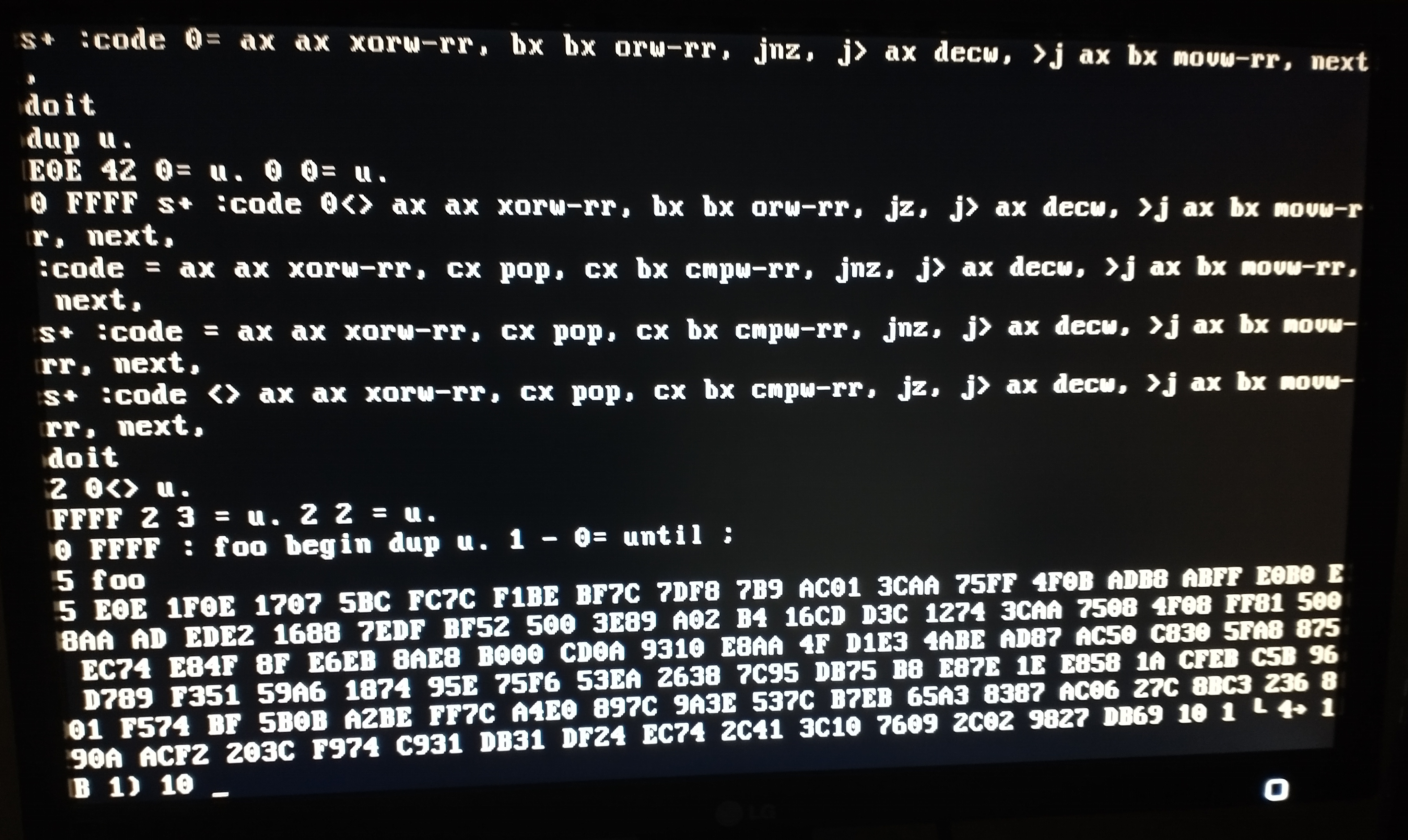

Comparisons

Branching is not that useful without any way to compare things. One common concern among all comparison words is turning a processor flag into a Forth boolean. Recall that, in Forth, booleans have all bits either set or unset:

: false 0 ;

: true FFFF ;

I chose to generate these booleans by first setting ax to 0, and then possibly

decrementing it based on the result of the comparison. This code can be factored

out as follows:

: :cmp :code ax ax xorw-rr, ;

: cmp; j> ax decw, >j ax bx movw-rr, next, ;

Then, to define a comparison, you just need to compile a jump that will be taken when the result should be false:

:cmp 0= bx bx orw-rr, jnz, cmp;

:cmp 0<> bx bx orw-rr, jz, cmp;

:cmp 0< bx bx orw-rr, jge, cmp;

:cmp 0<= bx bx orw-rr, jg, cmp;

:cmp 0> bx bx orw-rr, jle, cmp;

:cmp 0>= bx bx orw-rr, jl, cmp;

:cmp = cx pop, bx cx cmpw-rr, jnz, cmp;

:cmp <> cx pop, bx cx cmpw-rr, jz, cmp;

:cmp u< cx pop, bx cx cmpw-rr, jae, cmp;

:cmp u<= cx pop, bx cx cmpw-rr, ja, cmp;

:cmp u> cx pop, bx cx cmpw-rr, jbe, cmp;

:cmp u>= cx pop, bx cx cmpw-rr, jb, cmp;

:cmp < cx pop, bx cx cmpw-rr, jge, cmp;

:cmp <= cx pop, bx cx cmpw-rr, jg, cmp;

:cmp > cx pop, bx cx cmpw-rr, jle, cmp;

:cmp >= cx pop, bx cx cmpw-rr, jl, cmp;

For more complex conditions, we have the typical logical operators. As long as we're using well-formed booleans, there is no need to distinguish a separate set of purely logical operators — the bitwise ones work just fine.

:code or ax pop, ax bx orw-rr, next,

:code and ax pop, ax bx andw-rr, next,

:code xor ax pop, ax bx xorw-rr, next,

:code invert bx notw-r, next,

Yay, loops! What now?

So far, many words that could improve the workflow of editing the code in memory

just weren't possible to define, as they inherently use a loop. This changes

now. Firstly, let's define type, which prints a string:

: type ( addr len -- )

begin dup while 1 - >r

dup c@ emit 1 +

r> repeat drop drop

;

In my current workflow, the most recently defined block is terminated with a

null byte. Finding this location is necessary to append things to that block.

This is what seek does:

: seek ( addr -- end-addr ) begin dup c@ 0<> while 1 + repeat ;

It is then used by appending to set the srcpos and checkpoint

appropriately:

: appending ( addr -- ) seek dup u. srcpos ! move-checkpoint ;

Another useful thing is the ability to show the contents of a block and quickly estimate the address of a specific point in the code — as we don't have any real code editor, this is the first step of any patching endeavour. I chose to display the blocks in the typical 64-by-16 format, even though my blocks aren't formatted in any way and tokens often span such linebreaks.

Instead of line numbers, I print the address each line starts at. This is both

easier to implement and more useful. First, we have show-line, which shows a

single line:

\ cr emits a linebreak

: cr 0D emit 0A emit ;

40 constant line-length

10 constant #lines

: show-line ( addr -- next-addr )

dup u. \ line number

dup line-length type cr \ line contents

line-length +

;

This is then called 16 times in a loop by list. Since we don't yet have

do-loop, this is quite involved.

: list ( addr -- )

#lines begin

>r show-line r>

1 - dup 0= until

drop drop

;

Sometimes, we need to move some code around. For that, we'd need move. It is

like C's memmove, in that it copies the data from the right end, so that the

result is right even when the source and destination overlap. We'll implement

this with x86's rep movsb instruction, which is basically an entire memcpy

in one instruction. Let's teach the assembler about the rest of the string

instructions while we're at it:

: rep, F2 c, ;

: movsb, A4 c, ; ; movsw, A5 c, ; ; cmpsb, A6 c, ; ; cmpsw, A7 c, ;

This is then used by cmove, which copies data forwards.5 This wrapper is

somewhat long, as we need to save the values of si and di.

:code cmove ( src dest len -- )

bx cx movw-rr,

si ax movw-rr, di dx movw-rr,

di pop, si pop,

rep, movsb,

ax si movw-rr, dx di movw-rr,

bx pop,

next,

Next, we'll need cmove>, which starts from the end of the buffers and copies

backwards. The arrow > indicates that this is the right word to use if the

data is to be moved towards a higher address, i. e. to the right. To run such a

copy, we run rep movsb with x86's direction flag enabled. This expects the

registers to contain the addresses of the ends of the buffers, so we run the

copy itself in (cmove>), and then the actual cmove> is responsible for

calculating the right address.

: cld, FC c, ; ; std, FD c, ;

:code (cmove>)

bx cx movw-rr,

si ax movw-rr, di dx movw-rr,

di pop, si pop,

std, rep, movsb, cld,

ax si movw-rr, dx di movw-rr,

bx pop,

next,

: cmove> ( src dest len -- )

dup >r \ save length on return stack

1 - \ we need to add len-1 to get the end pointer

dup >r + swap r> + swap \ adjust the pointers

r> (cmove>)

;

Finally, move compares the two addresses and chooses the appropriate copying

direction:

: over ( a b -- a b a ) >r dup r> swap ;

: move ( src dest len -- )

>r

over over u< if

r> cmove>

else

r> cmove

then

;

Implementing fill is similar, and it's useful for erasing any leftovers after

moves.

:code fill ( addr len byte -- )

bx ax movw-rr,

cx pop,

di dx movw-rr, di pop,

rep, stosb,

dx di movw-rr,

bx pop,

next,

Another issue when editing code is determining whether a specific word was

already written. To handle that, I wrote words, which prints the list of words

known to the system. Recall the structure of the dictionary:

Word headers contain the name as a counted string, meaning the first byte stores

the length. count takes a pointer to such a counted string, and turns it into

the typical addr len representation:

: count ( addr -- addr+1 len )

dup 1+ swap c@

;

Given a pointer to a dictionary header, >name will extract the name out

of it:

1F constant lenmask

: >name ( header-ptr -- addr len )

cell+ \ skip link pointer

count lenmask and

;

We'll also need to check the hidden flag, as otherwise we'll encounter the garbage names introduced by our compression tricks.

: visible? ( header-ptr -- t | f )

cell+ c@ 40 and 0=

;

Our last helper words are space, which simply prints a space, and #bl (stands

for blank), which is the constant that stores the ASCII value of the

space.6

: #bl 20 ;

: space #bl emit ;

All of this is then used by words-in, which takes a pointer to the first word

in a list. This will make it easy to adapt once our Forth gains support for

vocabularies.7

: words-in ( dictionary-ptr -- )

begin dup while \ loop until NULL

dup visible? if

dup >name type space

then

@

repeat

drop ;

: words latest @ words-in ;

Parsing

I will eventually need to replace the codegolfed outer interpreter with one

written in Forth. This will let me add things like proper handling of undefined

words, the familiar ok prompt, but also vocabularies and exception

handling.8 The first step towards that is the parse ( delim -- addr len ) word, which will parse the input until a specified delimiter character is

encountered. For usual parsing, this would be a space, but if we set it to ),

we'll finally have comments.

parse stores the separator in a variable, so that helper words can use it.

variable sep

Parsing can end because we found a separator, or because we ran out of input, which is signified by a NULL byte.

: sep? ( ch -- t | f ) dup 0= swap sep @ = or ;

After the parsing loop ends, we'll have a pointer to the separator. If it is a

true separator, we want to remove it from the input — after all, ) does not

exist as a word. However, if we stopped because the input has ended, then we

must not advance past the null terminator. +sep handles this, and advances the

input pointer only if it doesn't point at a null byte.

: +sep ( ptr -- ptr' ) dup c@ 0<> if 1+ then ;

The loop in parse keeps two pointers on the stack. One doesn't move, and marks

the beginning of the token. The other is advanced in each iteration. At the end,

we save the moved pointer into >in, and then compute the length by subtracting

the two pointers.

: parse ( sep -- addr len )

sep ! >in @ dup begin ( begin-ptr end-ptr )

dup c@ sep? invert

while 1+ repeat

dup +sep >in ! \ update >in

over - \ compute length

;

This works when we want to parse a comment, but to parse a word, we actually

need to skip leading whitespace first. This is handled by skip, which also

takes the separator as an argument and advances >in so that it doesn't point at a

separator anymore.

: skip ( sep -- sep ) begin dup >in @ c@ = while 1 >in +! repeat ;

token combines the two.

: token ( sep -- addr len ) skip parse ;

This is then used by char, which returns the first character of the

following token — we can use this as character literals.

: char #bl token drop c@ ;

However, to include such a literal in a compiled word, we need [char]:

: [char] char lit, ; immediate

Finally, ( is an immediate word that runs a )-delimited parse and discards

the result.

: ( [char] ) parse 2drop ; immediate

Bare metal

Once the Miniforth bootsector was ready, I decided to do all my development and testing on a bare metal computer. All in all, I don't regret this decision, but getting to the point where I could save code on disk did take a few tries. I did take photos of the code, though, so retrying only took typing in about a kilobyte of source code again. A few attempts were ruined by typos made during this transcription, but apart from that I did have two bugs worth mentioning.

The first time around, I tried implementing branches before writing to disk itself. The branching code itself was perfectly fine, but my looping test wasn't. Try spotting the mistake:

: foo begin dup u. 1 - 0= until ; 5 foo

Show hint

The code crashed like this:

Reveal solution

The 0= consumes the loop counter on the stack, which means that each iteration

underflows further into the stack. Since there's no protection against this, the

code will be popping things until it starts overwriting code important enough

that it causes a crash.

The other bug was in the int13 word itself. As I've alluded earlier, I forgot

to save SI, which is the execution pointer for the threaded code. It crashed as

soon as it ran next. Ironically, if I wasn't so cautious and ran a

write-block as my first operation, most of the code would've been saved

🙃

Apart from bugs, there is another difficulty with running on bare metal: sharing

the code on GitHub. I solved this by writing a script, splitdisk.py, which

extracts the code out of a disk image. Since I'm booting off of a USB stick,

getting the code over doesn't take long.

Since there aren't any line breaks in there, I wrote a heuristic to split it

into a line per definition. Thanks to Python's difflib, it even preserves any

formatting adjustments made manually when extracting an updated version of a

block.

What's next?

Now that we have branches, many things become available as the potential next step. One important goal is to write a text editor, but some other improvements to our Forth will probably have to come first.

Meanwhile, I encourage you to try bootstrapping on top of Miniforth up to branching without using any additional assembled primitives. Not that there's any merit to limiting yourself like that, but it is an interesting problem. I'll explain my solution in a week's time, along with any substantially different ones found by readers like you. I've created a separate discussion thread for this problem, so please keep any spoilers out of the comments below the article 🙂

Hope you enjoyed this!

You might like some of my other posts, too. If you'd like to be notified of new ones, you can follow me on the Fediverse or subscribe to the RSS feed.

Also, I'd like to thank my GitHub sponsors for their support: Michalina Sidor, Tijn Kersjes, LunNova and Anders Murphy.

There is a slight difference from the standardized behavior,

in that my load merely repoints the input pointer, and the block will only

actually execute once just before execution reaches the top-level REPL.

It is now dawning on me that the reason it is usually called >in is

that it is usually an offset (>) that gets added to a separate base address

of the input buffer. Oh well.

It's not like that would be a disaster, though. Rerunning the code like that is a normal occurence after a bugfix.

If this was something like mov [0x1234], 0x5678, then the

exact order used is: opcode, ModR/M, address, immediate.

This is not the best name, as it is not what a C programmer would call a "move", but it is what the Forth standard uses, so I'll roll with it.

It is now dawning on me that I could've defined it with

constant instead. I'll probably change that when I bootstrap a proper text

editor.

Forth vocabularies, also known as wordlists, are a way segregating words into multiple separate 'dictionaries', which can be dynamically added and removed from the search order.

The exact aspect I'm concerned with is installing a top-level handler for exceptions that aren't caught. There's probably a way to make this particular aspect work without a new outer interpreter, but the other benefits are still there, so there isn't much point trying to figure this out.